By Nicole Walshe and Anne Mai Baan | EADI/ISS Blog Series

Narratives or the stories we use to set our perceptions and experiences in a larger context of meaning are powerful tools for both supporting civic space and engagement and oppressing them. As we are often not even aware of these narratives, changing them is not easy and requires much more than spreading information. A roundtable at the recent EADI/ISS conference “Solidarity, Peace and Social Justice” explored successful practical examples how a deeper change of narratives can take place in favour of positive social change and freedom of expression. Nicole Walshe and Anne Mai Baan summarize its recommendations.

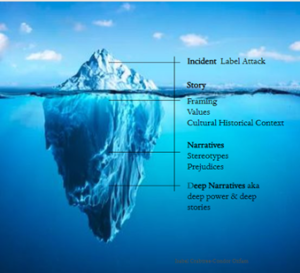

In our work to strengthen and support civic space worldwide (i.e. the space for freedoms of association, assembly and free expression) we often see that certain narratives are used to undermine the work of activists towards social change. Narratives – the collection of stories we intentionally or unintentionally use to set our experiences and observations in a larger context of meaning, and shape our understandings of the world – are like layered currents. Sometimes only a part of the narrative is visible, the tip of the iceberg, but beneath the surface it is connected to deeply held and shared social norms and values, history and culture which are often invisible and difficult to melt down.

We seized the opportunity at the EADI/ISS conference to understand different strategies to influence narrative currents. The virtual roundtable on solidarity-building narratives affirmed that such narratives can be powerful tools to protect and strengthen the space to practice our civic rights – as key enablers of peace and social justice. We also learned that narrative change work is about:

- Hope and Play. Narrative work finds creative ways to move people to new ideas and experiences, tapping into feelings of hope and visioning possible futures.

- Relationships and Understanding. It is a process of mutual learning – demanding openness to have one’s own mind changed too.

- Listening. It is most powerful when you reach out to those you don’t necessarily already agree with, to find shared values and meet in the middle.

- Co-Creating: It is a constant iterative process, asking interaction with all kinds of actors and individuals, finding expressions of solidarity to create a better future together.

- Showing, not telling. Narratives need to be embodied, and solidarity is best expressed through concrete actions.

- Moving beyond strategic communications: The end goal of narrative change work is a deeper level of social change based on power analysis and social norm change strategies.

So what does this look like in practice? Read about the approaches, tactics and lessons from Bulgaria, South Africa and Colombia….and how funders can support this work.

The importance of Hope – shifting perceptions in Bulgaria

For Fine Acts – a global creative studio for social impact – hope is the thread that cuts through all their work. Research about what makes people care reveals that opinions don’t change through more information but through compelling, empathetic experiences. Yana Buhrer Tavanier explained that if our messaging triggers fear and guilt, people will shut down. We need to communicate hope and opportunity to engage people and gather the positive and creative energy for change! Fine Acts applied this in their Love Speech campaign, which engaged 35 leading Bulgarian artists in a vast campaign against hate speech, which has been on the rise particularly against Roma, LGBTQI+ people and refugees. The campaign featured a series of urban art interventions, a participatory installation, a viral online video, and a large free-to-use collection of illustrations, and reached more than one million people, raising awareness of the implications of hate speech on wider society. Through creativity, playfulness, hope and wit, the campaign was able to engage people in a non-threatening way to shift perceptions of these marginalized groups and counter dominant hateful narratives.

Yana’s tip: – don’t let trying to do things the ‘perfect way’ hold you back – experimentation is just as good. Try, learn, adapt, learn and adapt again!

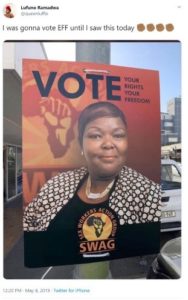

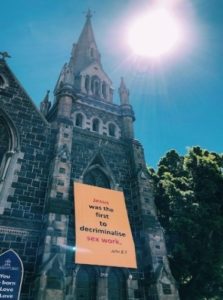

The importance of Play – challenging beliefs in South Africa

Narrative change work combines campaigning and communication strategies. In order to be effective it needs to focus on understanding the interests and psychology of those whose perceptions you want to change, and taps into culture, humour, history to connect with the audience on multiple levels. This also requires a certain amount of playfulness – in particular when serious and demanding human rights activism can lead to burnout or feelings of powerlessness. Ishtar Lakhani illustrated the creative and playful mixed approach through the example of raising awareness on the rights of sex workers in South Africa. The Sex Workers Education and Advocacy Taskforce (SWEAT) chose to focus on challenging the specific image of sex work pushed out by Hollywood blockbuster imagery. By instead showing the multiple working identities of sex workers – as mothers, carers, often combining different jobs – the campaign demonstrated that sex work is not the only work that sex workers (can) do. For example, SWEAT also seized the opportunity of the 2019 South African National Elections to deploy their creative activism and started a fictitious sex worker-led political party called SWAG. Through political party posters, convincing social media coverage and a campaign video with the one-liner ‘Your Rights, Your Freedom, Your SWAG’ they gained attention and public space to talk about the rights of sex workers and managed to get the two largest opposition political parties to include this as an issue in their election manifestos.

Ishtar’s tip – changing the language you use can sometimes create bridges to unexpected allies and new ways of looking at the issue. You can then jointly make a new narrative!

The importance of Relationships and Showing, not Telling – Human Rights outreach in Venezuela

Doing narrative change work can also be about using concrete action to show people what we mean when talking about rights. Often those concrete practical examples are precisely what pulls people towards social change activism rather than mere rhetoric and general statements about rights. In Venezuela two things came together to change the way a team of pro-bono lawyers did human rights outreach to communities. The team had already been facing narrative attacks labelling human rights proponents as ‘anti-Venezuelan’, and had been working on a series of events that would ‘materialise’ rights in ways beyond their traditional legal accompaniment. By offering opportunities for sports, music, and entrepreneurial training, for example. With the onset of COVID, the need to creatively rethink how they reached community members became even more urgent. So they held upcycling workshops to make PPE face-shields, began partnering with community kitchens, and formalized a position for creative community activism. These creative approaches resulted not only in more effective community engagement, but also prompted reflections on what it means to be lawyers and how they might give a face to human rights that resonates more with the lived experiences of the communities they work in.

Lucas’s tip: Appeal to people’s ideal collective future, to reveal how much the values underlying these visions of an ideal society align. Narrative success depends on making relationships and experiences the ends of your project, not the means.

The importance of FAILing and funding failure!

FAILing, or a First Attempt In Learning, is something James Savage from the Global Fund for Human Rights encourages all funders to not only be excited about, but to incentivize and enable. He suggests some key points for funders who are interested in supporting narrative change work to bear in mind:

- Focus on the process, not product, and fund the process. Work on shifting norms, perceptions and deep currents in society has different timelines and measures of change!

- Embrace risk, unpredictable outcomes and experimentation. ‘Success’ is redefined by the learning, iterations and ‘FAIL’ing forward.

- Understand the objective of a funder as ‘accompanying a learning journey and building of narrative power’, and translate this directly into an accountability framework focusing on changes and learning instead of impact.

- Resource local narrative changemakers & foster connection for mutual support, learning and collaboration. Lots of small initiatives may be the answer.

- Support an infrastructure of narrative work with the means to widely disperse and deeply immerse narratives over time that shape how societal norms are set.

James’s tip: Funders need to be prepared to FAIL forward and to support others to FAIL forward.

Solidarity in Narratives, Narratives for Solidarity

Humans tend to assemble mutually reinforcing stories in order to establish common sense and construct shared beliefs or truths about people, places, communities, cultures and their understandings of rights and social justice. Narrative work is about changing what is ‘known’ about a group of people, or about a situation. It is, however, not about ‘convincing’ people; rather about building new and different relationships and understanding. Co-constructing narratives can be a key way to connect with different constituencies and build solidarity across groups, including those that didn’t start out with the same perspective or agreement. It is as much about story-listening as story-telling. And the stories continue to be written:

- Get inspired by the Love-Speech Campaign and all the other campaigns run by Fine Acts

- Read Ishtar’s journal article on creatively fighting for the rights of sex workers in South Africa and listen to Ishtar’s tips on creative activism

- Explore the innovative approaches to of JustLabs

- Dive into more of James’s reflections on narrative work

- To learn more about Oxfam’s narrative work and journey contact Anne Mai Baan and Isabel Crabtree-Condor

This article is part of a series launched by EADI (European Association of Development Research and Training Institutes) and the Institute of Social Studies (ISS) on topics discussed at the 2021 EADI/ISS General Conference “Solidarity, Peace and Social Justice”. It will also be published on the ISS Blog

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the EADI Debating Development Blog or the European Association of Development Research and Training Institutes

Nicole Walshe coordinates Oxfam’s Knowledge Hub on Governance & Citizenship (KHG&C) – a network for staff working on themes of governance & citizenship, with a specific focus on civic space, fiscal justice and active citizenship. She does this together with the inspiring KHG&C Core Team, who are based in The Netherlands, Bolivia and Vietnam. Nicole is passionate about the topics of civic space and human rights and combining these with influencing tactics and strategy, and has a keen interest in supporting knowledge and learning processes that can help us take action and make strategic decisions based on what we observe and learn.

Anne Mai Baan is a Knowledge Broker on Civic Space & Narratives in the KHG&C Team at Oxfam. This position is all about convening connections and building relationships across Oxfam’s network on the topics of civic space and narratives. Within the knowledge Hub we find creative and inclusive ways to make different forms of knowledge (experiences & expertise) more visible, accessible and useful for greater reach, impact and influence! Anne Mai is passionate about issues of power and exclusion, the way language shapes our experiences and the impact of competing narratives in humanitarian and development contexts.

Header Image: Atanas Giew for Fine Acts