By Andy Sumner, Laura Camfield, Keetie Roelen and Lukas Schlogl.

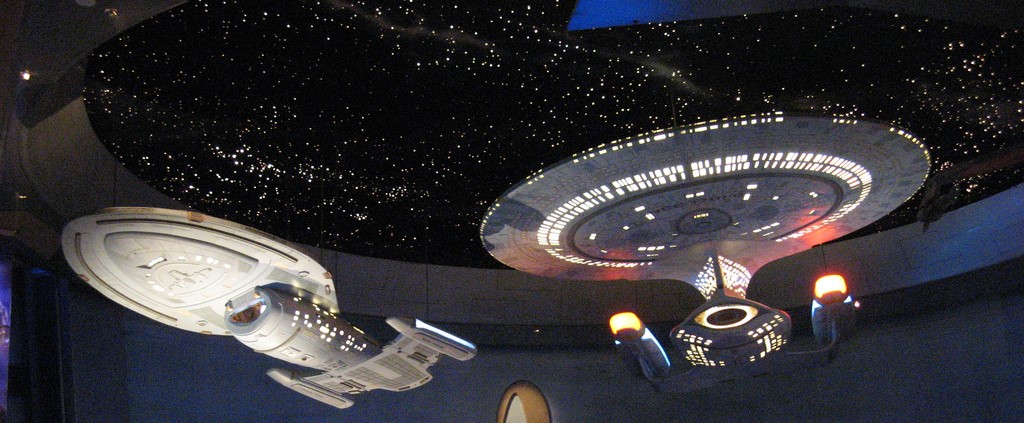

‘Q-squared’ is a best-selling Star Trek book from the mid-1990s (yes there are Star Trek books, not just films and TV series) about someone who has the power to tamper with time and reality resulting in three parallel universes that intersect. Just a few years later the term came to prominence in three parallel universes in development studies (spooky, eh?). Those parallel universes being qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods researchers.

The discussion of mixed methods research – meaning in the first instance research that combines qualitative and quantitative methods in some way – was prominent in development studies in the 2000s and extended into discussions of cross-disciplinarity in special issues of World Development and the Journal of Development Studies, in edited volumes by Ravi Kanbur and by David Hulme and John Toye as well as the very large number of working papers of the ‘Q-squared’ project led by Paul Shaffer at Trent University as the Captain of the Enterprise. The benefits proposed related to generating a more holistic understanding of how poverty is experienced and transferred from generation to generation. Mixing methods also offered the potential to challenge conventions within international development such as the use of people’s income as a proxy for their wellbeing. Finally, it could act as a valuable communications tool by reuniting people’s stories with their data – what does it mean to be poor in particular contexts? How does it feel to be continuously on the edge of poverty? What does living below a dollar a day really look like?

Much of the debate then was between development economists and non-economists and thus the focus was often what can mixed methods bring to the study of economic-related development questions and poverty research in particular, for example, by accessing data that can’t be reliably collected through surveys. It was in some instances a certain set of methods being mixed – household surveys and participatory research – and in other instances, such as the World Development Special Issue noted above, studies involving ethnographic work.

So, ten years ago one might be forgiven for thinking mixing methods would have become the new orthodoxy in studies of development by now. Here is how one scholar summed it up in the early 2000s:

The desirability and usefulness to combine qualitative and quantitative methods to analyze social realities is pretty much accepted in the literature today; voices of segregation – still quite powerful in the 1980s – have subsided notably. (Hentschel, 2003: 75)

A decade or so later, mixed methods does not seem as prominent as it was even within the field of economics-related development studies. One could speculate on the various reasons why mixed methods has retreated somewhat. Candidates might include the currents in development economics itself, fostering the rise of Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) which raised questions over the value of qualitative methods in micro economic-related questions (why use anything else if you can have incontrovertible ‘proof’). The overall shift in economics towards the micro -of which RCTs are the most visible trend – may well have diverted attention from mixing methods.

In light of the above, our recent EADI webinar revisited those earlier debates on mixed methods and asked what do we understand to be ‘mixed methods‘? We discussed the state of mixed methods in development studies, and the parallel worlds of different researchers, and drew examples from the use of mixed methods in the study of poverty, inequality and economic development. We looked at examples of innovative uses of mixed-methods research in development studies and discussed the challenges arising not least how rigour is to be judged.

The webinar drew on insights and resources of a recent interdisciplinary workshop in London co-organised by EADI, the Development Studies Association, King’s College London, the ESRC Global Challenges Global Poverty & Inequality Dynamics research network and the Comparative Research Programme on Poverty (CROP).

The good news is: if you missed the webinar you don’t need to beam yourself to a parallel universe or tamper with time and reality as the good folks at EADI have uploaded the webinar here. There’s also a collection of mixed methods resources including presentations from the webinar and the workshop here and here. And, of course, the real ‘Q-squared’ – the Star Trek book – is available from all good book stores in all parallel universes.

Andy Sumner is Reader in International Development at Kings College, London

Laura Camfield is Professor of Development Research and Evaluation at the School of International Development, University of East Anglia

Keetie Roelen is Research Fellow and Co-Director of the Centre for Social Protection at the Institute of Development Studies (IDS), Sussex

Lukas Schlogl is University Assistant in Comparative Politics Analysis at the Department of Political Science, University of Vienna

Image: Alexander Tsang