By Stacey Scriver and G. Honor Fagan | EADI/ISS Blog Series

There are right and left, radical and conservative social movements at work in today’s volatile and unequal world. Whether directed towards a transformative social justice agenda or not, social movements themselves do not exist outside of the structures of power. A growth in populist politics, a resurgence of religious movements with conservative agendas on gender and sexuality, and new male supremacist ideologies remind us that gender justice is an extremely challenging and ongoing struggle. Even among social movements directed towards deep social justice, gender inequality remains a key concern, since gender-relatedinequalities persist, both within the movements themselves, as well as in their recognition, support and the response to them.

The Sustainable Development Goals represent the blueprint to achieving a better and more sustainable future. SDG 5 is particularly relevant to considerations of gender and social movements. It is clearly recognised that to achieve sustainable growth, gender equality is necessary. This includes the removal of barriers to women’s empowerment, such as the common and pervasive experience of violence against women or gender-based violence. It also implies re-shaping power structures through the inclusion of women in leadership roles, both within government and in economic activities.

Social movements can be powerful actors in efforts to protect and expand human rights, including gender inequality. Further, social movements are vital training-grounds for leadership and political engagement: many who ultimately take up positions of power within societies initially learned skills in negotiation and communication and built their reputations through work with social movements. They thus also offer a pathway for women to achieve political and economic status.

Gender in Social Movements for Economic, Environmental and Social Justice

Despite the potential of some social movements to contribute towards a gender-just world, inequalities persist within the structure and organisation of many. Leaders are most often men, and often men who ascribe to a culturally acceptable form of masculinity. Women often take on the ‘house-keeping’ roles within social movements, such as organising recruitment and developing campaigns, or ‘soft’ activism, such as maintaining relationships behind the scenes. Consequently, those whose voice are heard most and who consequently benefit most from such public profiles are more likely to be men, limiting the benefits of participating in social movements for women. In short, the working culture of these movements and their pedagogical methods do not create gender parity in membership and decision-making unless they are ‘engendered’.

Many social movements neglect to address the question of gender. For instance, in movements for peace and reconciliation, concerns perceived as relating only to women are often relegated to a secondary status. Peace movements may perceive conflict-affected gender-based violence, including the propensity for increases in intimate partner violence in the context of conflict, as being a second-class category of concern. That is, to be addressed once the ‘bigger’ issues of, for instance, organised violence by paramilitaries, are resolved. This is despite gender-based violence affecting more individuals than organised violent attacks.

The failure to apply a gendered approach to social issues and to create equality within social movements may thus replicate inequalities within the movement itself. This undermines the potential for social movements to be a space wherein women can develop key skills in leadership, shape demands for justice, and develop trust with publics. There is a crucial role for feminists and gender justice activists to create change within social movements, even those advocating social or environmental justice and sustainable development.

Gendered Social Movements

While women have historically taken on important, if often under-recognised, roles in social movements, with examples including the labour movements of the 19th and 20th Century, ‘women’s movements’ have also been active in combating gender discrimination, from suffrage movements to Violence agains Women (VAW) movements. There have been notable successes. The Global Campaign of the early 1990s, and the organisation of the Vienna Tribunal, achieved a significant shift in the human rights agenda, with the explicit recognition of violence against women as a human rights violation.

However, women’s or gender movements also face particular barriers due to gender bias, stereotypes and inequalities. Being perceived as having particularist goals or lacking sufficient political allies in positions of power has limited the successes of often vibrant women’s movements in terms of translating knowledge raising and public activism into direct political and/or economic gains.

Gender justice is too important to be siloed as a ‘women’s issue!

Put simply, social movements are critical components of thriving democracies, and even more critical where democratic accountability is on the wane. However, persistent gender inequalities within social movements, mean that social movements themselves may not be representative of the needs of its members. Social movements need to engage in critical reflection and restructuring to ensure that they are themselves gender just.

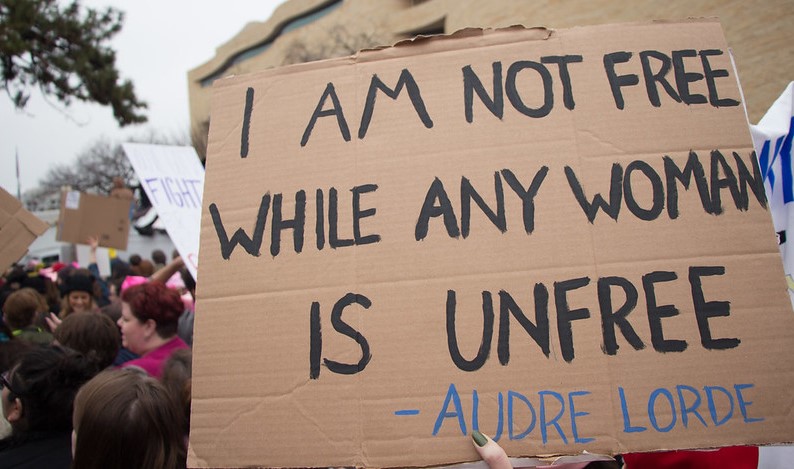

Moreover, adequate recognition that equitable social change and sustainable development requires gender equality must be central to the organising principles not only within social movements but also across those seeking social justice. Additionally, gender justice is too important to be siloed as a ‘women’s issue’. Allyship between explicitly gendered movements and those focused on other kinds of social justice change is needed. Transformative social change is necessary for long-term and sustainable development and social movements have an important role to play; gender justice, within and between social movements, is a prerequisite.

If you are you interested in discussing gender and social movements further, consider submitting to our harvest panel “Gender Movements and Social Justice” at the EADI/ISS General Conference 2020

Our panel seeks to deepen understanding of the role of gender movements, and gender in movements (including gender solidarity), working towards peaceful, equitable and just communities and societies. We welcome papers that engage with the issues of gender justice and social movements through a variety of perspectives and approaches. Contributions from early career researchers, established academics, and practitioners, including empirically and theoretically-based draft papers, are all welcomed.

This article is part of a series launched by EADI (European Association of Development Research and Training Institutes) and the Institute of Social Studies (ISS) in preparation for the 2020 EADI/ISS General Conference “Solidarity, Peace and Social Justice”. It was also published on the ISS Blog.

Stacey Scriver is co-convenor of the Gender Justice Working Group of EADI. She is also a lecturer in Global Women’s Studies in the School of Political Science and Sociology and Director of the MA Gender, Globalisation and Rights at the National University of Galway, Ireland

Honor Fagan is co-convenor of the Gender Justice Working Group of EADI. She is also a Professor of Sociology at Maynooth University, Ireland.

Image: Alejandro Adam on flickr