By Amélie Foko’o Magoua, Anna Chevalier, Cassandra Ajufoh and Tomaso Ferrando

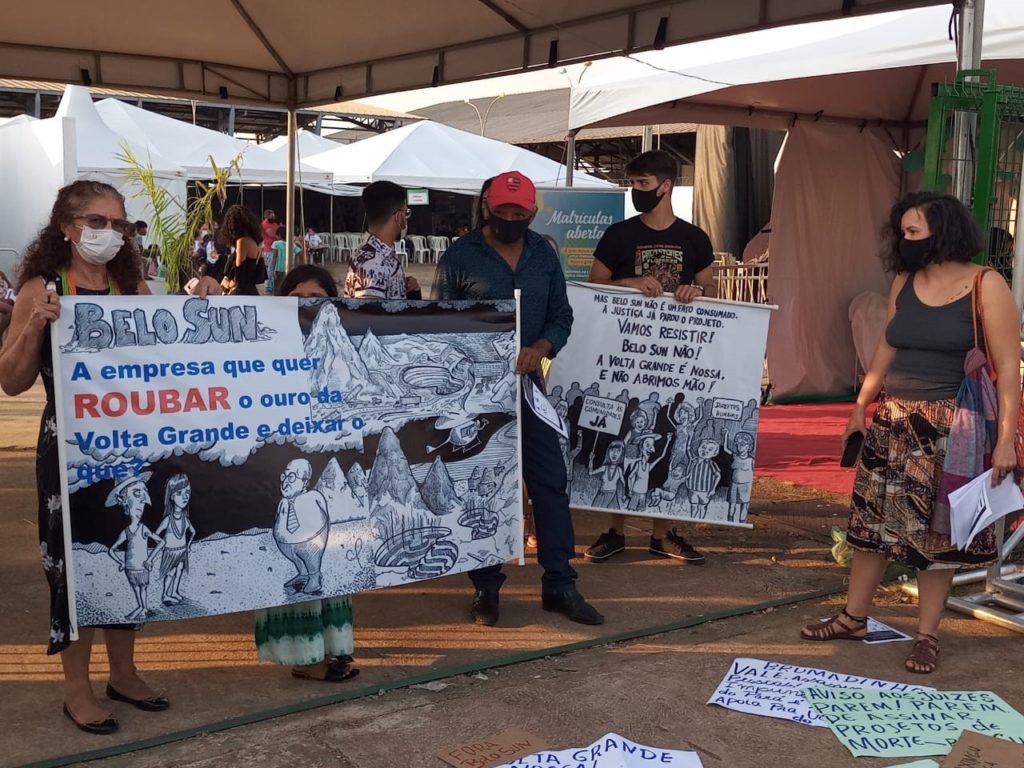

On June 5th, a group of inhabitants of the agrarian reform settlement Ressaca in the Brazilian state of Para organized a collective action to take back public land previously turned over to Belo Sun Ltd, a Canadian mining company. The action, conducted with the support of indigenous communities and actors from across the Amazon region, aimed at vindicating the right of people to the integrity of their territories and opposing the way in which regulators, politicians and private companies were sacrificing them in the name of gold extraction and global trade in natural resources. Moreover, the action was a clear signal against the limits of national legal processes and a consequence of a frustrating visit to public and private actors in the European Union.

For centuries, Indigenous peoples, rural communities and Quilombolas, i.e. descendants of enslaved Black and Indigenous Peoples, in Brazil have had a lot to endure in the name of modernity development, economic growth and progress. This is especially true in the state of Pará, where their rights have been continuously set aside in the name of grandiose projects and modernization. This particular land reclamation, for example, concerned an area already shaped by the completion of the Belo Monte dam project few years before and recently threated by the realization of the largest open pit gold mine in the Amazon.

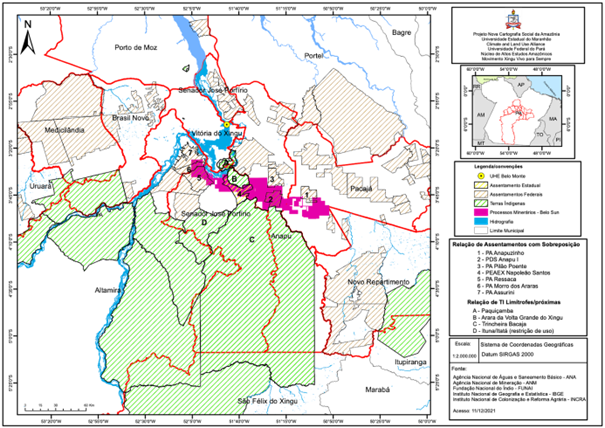

The Volta Grande Project, as this mining operation is called, is a proposed open-pit gold mining project right on the banks of the Xingu River, where it the Belo Sun company would occupy over 2,000 ha of public and community land downstream to the Belo Monte dam, directly benefiting from the reduced capacity of the river and the dry terrain that the dam has left behind. This highlights that not only large-scale infrastructures and extractivism go hand in hand, but that they are also strengthened by and dependent on infrastructural development, regulatory changes and transnational institutional silence.

Mining and extraction are favoured by national legal inactions and actions

The Volta Grande situation is evidence of the way in which legal actions and inactions are key for supporting the realization of projects that clash and collide with the visions and aspirations of local communities. On the one hand, law indicates the process for and provides the legitimacy behind the provision of any concession. In the Volta Grande area, one of these resettlements is the Projecto de Assentamento Ressaca,also known as PA Ressaca, whose territories overlap with the area of interest to Belo Sun. As a consequence, it is denounced by Brazilian organizations and local people since 2017 the National Agrarian Reform institute (INCRA) has been negotiating the transfer of a part of the PA Ressaca to Belo Sun.

Despite the fact that Belo Sun’s installation licence to operate was judicially suspended as we discuss below, and despite the opposition of local actors, the mining company and INCRA signed an agreement in 2021 which recognized the possibility for Belo Sun to install its gold mining project within federal public land in the Volta Grande region. With a strike of a pen, territories became empty and available.

On the other hand, law can be inaction, as in the case of the slow recognition of indigenous lands and territories, regardless of the requirements of article 231 Brazilian constitution. An incomplete and insufficiently funded demarcation creates the conditions for private interests and claims to be advanced and crystallized, increasing the scope for legal protection. In the specific case of the Paquiçamba indigenous lands near the mining project, demarcation has yet to be finalised, which opens the doors to land conflicts and increasing violence.

Moreover, law can also be eluded or non-enforced, as evidenced by the fact that some of the land where Belo Sun encroached was illegally acquired. In the case of resettlement projects, like the PA Ressaca, Brazilian law imposes certain conditions which would need to be met in order to acquire certain plots. This includes the existence of a title which can only be transferred 10 years after it is issued by INCRA. However, communities have been pointing out that these conditions have not always been fulfilled by Belo Sun which was not sanctioned, signalling yet another way in which national law and its actors can shape territories, lives and spaces of resistance.

At the same time, legal procedures can also offer an opportunity and space for and intervention, like the recent judgement by the court of appeal for the state of Pará, On 25 April 2022. It has confirmed the suspension of the project in the absence of an adequate environmental licence and the failure to guarantee the free, prior and informed consent of all indigenous communities directly or indirectly affected by the project. The mere request for more studies and more engagement, however, does not escape from the logic of transforming territories into spaces of (more sustainable) extraction. A truly transformative approach, it seems, cannot be reached from within the existing rules of the game, but requires the capacity to embed the case of Belo Sun in the transnational network of actors, laws and policies that creates the conditions for such project to be ‘needed’.

A globally-defined territorial struggle beyond business and human rights?

Brazilian political economy and laws are partly responsible for a series of conditions that will undoubtedly lead to an increased pressure on the lands and pose a risk to the livelihood of indigenous groups and local communities. However, it is essential to highlight that what is happening in the Volta Grande region is linked with actors and policies in many countries around the world, which facilitate or benefit from the exploitation of the rivers, the extraction of gold and its trade.

For example, European companies were key to the construction of the hydroelectric dam of Belo Monte. Moreover, Belo Sun Mining Corp. is a Canadian-based company with investors based in the United States, Luxembourg and Singapore. In addition, Switzerland is the main recipient of gold extracted in the Amazon basin. For these reasons, when we think about the past, present and future of the Volta Grande, it is not enough to question the responsibility of the Brazilian government and the local authorities. The struggle is a local one as much as a transnational (and European Union) one.

If this is the prism of analysis, it becomes key for non-Brazilian actors to create the conditions to engage with legal frameworks and actors whose actions – or omissions – are directly affecting these territories and their ecosystems. We therefore need to look at the Volta Grande as part of transnational value chains where gold, finance and regulations cross borders and jurisdictions. Lives, territories and the ecological complexity of life in the region must be embedded in much more than the specific commodity chain to which they belong, but in the broader political and rhetorical framework that reproduces the idea of extractivism as a source of economic development, and that subordinates territories in the Global South to the vision and needs of wealthier countries and their actors.

The vision of the Volta Grande uphold by law and global value chains is, in our opinion, incompatible with the vision, the rights and the aspirations of the people on the ground. But also with the need to radically redefine patterns of production and consumption. In this sense, the final goal should not be that of legitimizing the transformation of the Volta Grande region into a global asset of consumption by simply promoting the adoption of human rights principles or the goals of sustainable development. The goal should be that of reflecting on incompatibilities, inherent tensions and limits of our actions. And to think about law not only as an instrument of transnational governance, but one of the ways in which alternative horizons and visions can be built and consolidated.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of the EADI Debating Development Blog or the European Association of Development Research and Training Institutes.

Amélie Foko’o Magoua, Anna Chevalier and Cassandra Ajufoh are Masters’ students of the Masters of Law and of the Sustainable Development Legal Clinic at the University of Antwerp.

Tomaso Ferrando is Research Professor at the Faculty of Law (Law and Development Research Group) and the Institute of Development Policy (IOB), University of Antwerp.

Title Image by Xingu Vivo Movement