By Tomaso Ferrando and Giedre Jokubauskaite / Debt and Green Transition blog series

This post introduces a blog series where multiple authors explore the role of debt as one of the most popular financial tools behind the ‘green transition’. Green and sustainability bonds, green microfinance, insurance and loan-enabled ‘loss and damage’ finance, are but a few of many variations of the governance logic, which uses debt to ‘green’ the economic system, while at the same time fuelling the financial and economic structures that lead to ecological destruction and a breakdown of social cohesion in the first place. If debt is so key, it must first of all be understood in its legal or financial construction and, more importantly, in the material and ideological implications that its use produces and consolidates.

Indeed, debt is much more than a state of owing money: it is the source of power of a creditor over a debtor, an obligation that often transcends generational boundaries, and a relationship that cuts across geographies. Debt is also a central element in the establishment and reproduction of globalized racialized capitalism. In the past, it was through loans that the crowns provided support to the colonizing missions and the appropriation of remote land. Debt was the yoke that was imposed on the Haitian people after they conquered their independence from the French occupation, and on several other countries as soon as they obtained their formal political independence. Debt is the raison d’etre behind the Club of Paris and the billions in interest that are paid on an annual basis by countries in the Global South for agreements concluded decades ago by illegitimate governments or in conditions of financial distress.

Debt is not only the past, but the present of a financialized capitalist system that has learned little from the 2008 financial crisis as a collapse rooted in the instability of expanding debt and mortgages and fueling this process by means of financial speculation. Despite being as old as capitalism, debt and indebtedness are increasingly promoted as new tools in the promoting of economic growth and the (re)construction of a post-covid19 world that is also in the midst of the ecological breakdown. For instance, in the NextGenerationEU (NGEU) plan, debt plays a key role in EU’s 800-billion joint post-pandemic ‘Recovery and Resilience’ instrument.

These trends appear to be increasingly celebrated in the policy-oriented literature. In the last years, we have been reading a wide range of contributions praising the expansion of labelled bonds (green, blue, municipal, sustainable, pandemic…), promoting the proliferation of green micro credits as an opportunity to support sustainable transitions of smallholder practices, or celebrating the capacity of . public and private actors of attracting climate and biodiversity finance by means of debt for nature swaps and other ‘innovative’ financial instruments. We have also read about the risks of greenwashing and low standards in a context of asymmetrical information, the political nature of defining a taxonomy for green investments and green bonds, and the need for accelerating the flow of private and public resources by means of new instruments and more political coordination.

How is debt shaping the world?

Yet, not enough attention has been paid to the role that debt and indebtedness have played in shaping the world of today, nor to the role that they are playing in shaping both the imaginary of the future and the practices of the present. If debt and interest repayment are central to capitalism as an expansionist process aimed at the continuous multiplication of the invested money, the normalization of debt and indebtedness as pillars of the ongoing transition should not be overlooked, along with the way in which it silences alternatives and legitimizes the status quo.

To start unpacking these issues, a group of interested scholars organized two roundtable sessions at the 2022 Law and Society Association Global Meeting in Lisbon, where participants shared their research and concerns. This discussion has inspired us to propose this blog series, which we hope will inform future conversations. While many examples and issues were discussed as part of the roundtables in Lisbon, the posts included in this series focus on the chosen, specific ‘green’ debt instruments or modes of funding green transition, and they question the new power dynamics, relationships and rationalities created in this process. The topics covered are: green transition and blended finance (by Biggar); a process of certifying ‘greenness’ of bonds (Garcidueñas Nieto); (a lack of) public participation standards in green financing (Herrera); green microfinance (Huybrechs); debt underpinnings of private sector mobilisation for green transition (Jokubauskaite), blue bonds (Onat Kiliç); and loss and damage finance (Rossati).

Based on the discussions we had in Lisbon and on the analysis in the blog posts included in these series, the following four lines of inquiry have emerged, which we propose should be interrogated by policy and research going forward:

- (Re)distribuve effects of debt. If debt establishes a relationship of subordination between debtors and creditors, what are the redistributive implications of treating the ecological deficit with debt? If debt is a form of rent seeking that has contributed to the unequal distribution of value, power and ‘development’ across geographies, how is it playing in the context of the transition?

- Intergenerational (in)justice of debt relationships. How does the intergenerational nature of indebtedness dialogue with the request for intergenerational and intragenerational justice associated with the responses to climate change and the ecological crises, but also with the conversations around odious and illegitimate debt and the unjust indebtedness of the Global South?

- Ex/inclusion dynamics in transitional measures based on debt. Given the financial structure of debt as a repayment of principal and interests often with the creditors’ protection provided by collateral assets or guarantees, and given the role that risk and credit rating play in the allocation and repayment of funds, who can participate and who cannot participate in the deb-based transition?

- Competing visions of the world beyond transition. Is debt compatible with all visions of the transition, or are there models and pathways that are incompatible with the functioning of debt and, therefore, are excluded by a transition financed by means of indebtedness?

These posts, we hope, are just the beginning of a broader and longer conversation among academics, civil society and policy makers, and we look forward to build spaces and opportunities to foster convergence and stronger understanding of the link between indebtedness and the climate breakdown, and the way beyond both.

Tomaso Ferrando is research professor at the Faculty of Law (Law and Development Research Group) and Institute of Development Policy, University of Antwerp. He researches the legal construction of the global food systems, the role of law in global production networks, and the co-optation of the ‘green’ transition. Currently, he is a member of the Legal Action Committee of the Global Legal Action Network (GLAN), where he is in charge of the land rights’ thematic area, and the President of FIAN Belgium, a non-governmental organization engaged in the promotion of the right to food and food sovereignty.

Giedre Jokubauskaite is Senior Lecturer at the University of Glasgow.

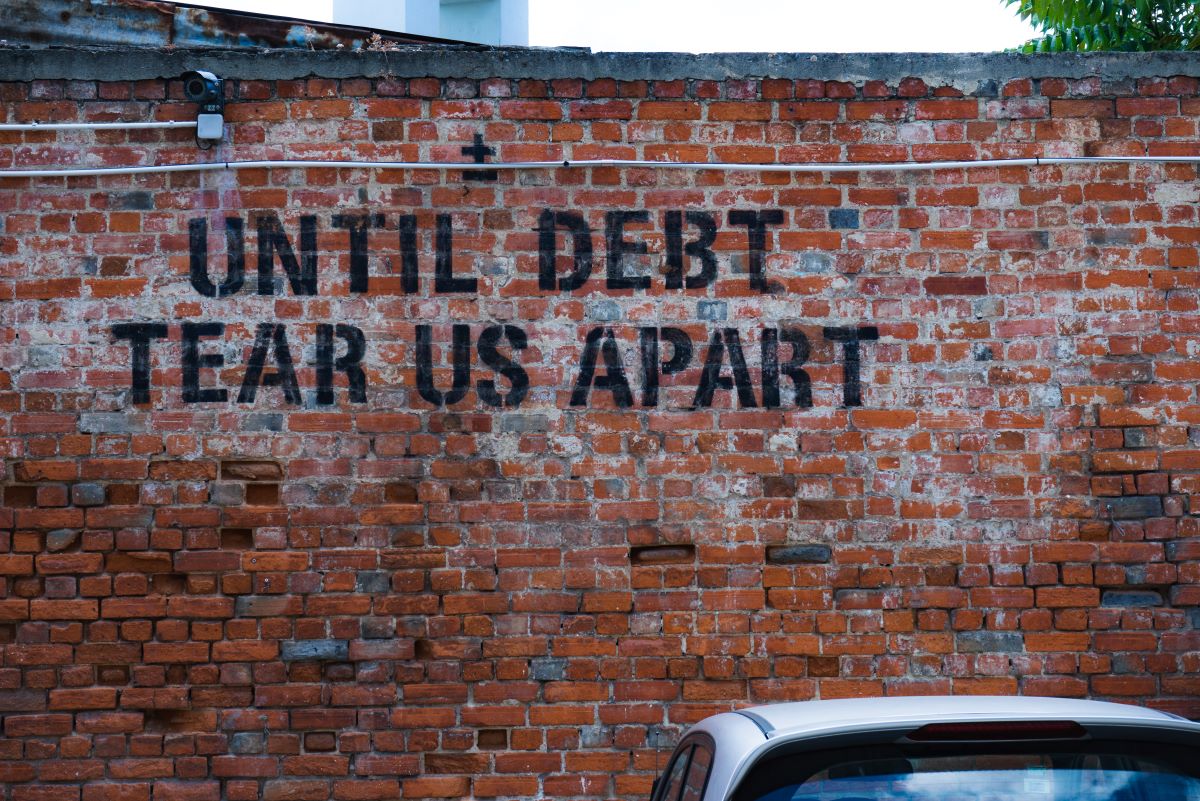

Image: Ehud Neuhaus on Unsplash