By Mette Fog Olwig, Jacob Rasmussen, Lone Riisgaard, Christine Noe, Geetika Khanduja, Peter Taylor, Herbert Hambati, Lisa Ann Richey, Chris Büscher and Paola Minoia / New Rhythms of Development blog series

Development Studies has long operated with binaries such as “developed/developing” and “traditional/modern” that foster implicit assumptions of Northern superiority. As a result, research projects taking place in so-called “developing countries” tend to ask different research questions and use different methods leading to types of theories that differ from those concerning so-called “developed countries.”

Furthermore, the size of development research funding varies between different countries, with larger amounts of funding traditionally being targeted towards development research by countries in the Global North than by those in the Global South. As a result, development research at Southern universities relies heavily on external donor funding, with Northern universities and funders potentially setting research agendas not just internationally, but also locally. This can lead to a “cognitive lock-in” with alternative worldviews, modes of knowing and ways of living being sidelined both in the Global North and Global South.

Based on conversations and discussions at a “seed panel” at the recent EADI 2023 New Development Rhythms conference and drawing on our collective experience and research, we explore here how development researchers can challenge the homogenization and hegemonization of knowledge production, foster a multi-directional flow of learning across the North and South and question pre-defined ideas of development. Our focus lies on one particular aspect, namely the research project design.

Co-designing Research Projects

Partnerships and co-creation of knowledge between Northern and Southern research institutions is increasingly emphasized and valued within development research. Several funding bodies in the Global North require North-South collaboration, and some countries in the Global South require that research projects be registered locally and include a local institutional collaborator to obtain research permits. This has increased opportunities for researchers in the Global South, especially because partnering for many is the primary, and often only, way to access funding.

Yet, as a result of the asymmetric power relations involved, such partnerships raise difficult questions, in particular in relation to equity and inclusion. This calls for novel approaches, and indeed important work to this end is ongoing at Global South universities and research institutions, but there is a need to continuously and critically examine such research partnerships.

One key problem with North-South research collaborations is that they tend to be based on projects that have already been designed, often in the North, before the collaboration is put in place. The overdependence on Northern scholars must be prevented because true collaboration requires equal terms. For research to have more impact and facilitate mutual learning, project proposals should be co-designed from the very beginning. Such co-designing could be fostered by establishing networks that can enable researchers to get to know each other before a specific call.

Another important factor relates to the financing and institutional set-up, which must encourage equal partnerships and consider local institutional cultural and financial structures – there are rules and regulations that apply on both sides. Furthermore, to build trust, there needs to be clarity regarding intellectual property rights and work distribution. Because of the extreme pressure to publish there is a risk of Northern scholars being mostly focused on obtaining local data, and not on local expertise and analysis. For scholars in the South there can be a thin line between collaborating with and becoming a facilitator for foreign research teams (processing research permits, assisting fieldwork etc.). Also, there is a danger of becoming involved in research that is not locally relevant and/or of interest to scholars in the South, when projects are already fully designed in the North.

Long-term Mutual Learning and the Development of Institutional Capacities

Key to the debate on North-South research partnerships are “tensions between short-term academic excellence recognition and longer-term capacity-building objectives.” Many research organizations in the Global South struggle to ensure sustainable sources of funding, and this influences their ability to build institutional capacities. The increasing dependence on project-based funding further contributes to this problem. One way to address this tension is to continue working with the same partners in consecutive projects. It is important that collaborative research projects include multi-directional skills building and learning. This can help address the prevailing unequal conditions for scholars that reinforce the already existing divides. If partners do not invest in building strong collaborations, there is a likelihood that they will not have a pool of good partners in the future. Multi-directional skills-building can for example be done through collaborative project management as well as writing, supervising, disseminating and doing fieldwork together.

Study Design: Data, Methods and Theory

In addition to reexamining the equitability of research partnerships, there is also a need to rethink study designs in relation to empirical data, methods and theory. This could be done by:

- Appreciating knowledge that already exists locally – e.g., via citations and building future research on this knowledge.

- Critically examining and challenging when and why cases from the North and South tend to be treated differently, and why we tend to ask different questions and use different methods in different places.

- Structuring inclusion as part of the collaborative research process, e.g., requiring co-authorship on publications across North- and South-based partners.

- Holding ourselves accountable to the same ethical standards regardless of what we are studying and where.

- Building general theoretical concepts from empirical research in the Global South.

- Redefining the object of study and “study sites” so that they cut across national boundaries and North-South divides. This could be done, for example, through multi-sited, online- and event ethnographic research focusing on transnational social movements, complex networks of social and economic relations, and intricate family ties that transcend the divide.

- Rethinking dissemination and dissemination channels to challenge traditional knowledge hierarchies and make more efforts to facilitate the dissemination of research locally (as we already do internationally), including connecting with governments, other research groups, practitioners and the general public.

Taking a step back from focusing on outcomes to instead treat the process of constructing and implementing a research project at a meta level, we can ask: “How can research projects be strategically designed to challenge the North-South Divide?” To read more about the different projects in which the researchers are involved, please see:

- Universal Aspirations vs. Geopolitical Divides: Imagining the World as a “Post-Millennial” in the SDG Era

- SWASH Sustainable Wastewater Systems for Ghana

- Producing alternative green futures: Exploring interconnections between green transitions and socioeconomic and political organization

- NEPSUS New Partnerships for Sustainability

- Pathways to impactful and equitable partnerships in Research for Development: A co-created, action-learning initiative

- Everyday Humanitarianism in Tanzania

- Geothermal Village: Smart/off-grid Geothermal stand alone, cascade-use systems

- Eco-cultural pluralism in Ecuadorian Amazonia

Mette Fog Olwig is Associate Professor at Roskilde University, Roskilde, Denmark

Jacob Rasmussen is Associate Professor at Roskilde University, Roskilde, Denmark

Christine Noe is Associate Professor at University of Dar es Salaam, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania

Lone Riisgaard is Associate Professor at Roskilde University, Roskilde, Denmark

Geetika Khanduja is Project Officer at Southern Voice, Delhi, India

Peter Taylor is Director of Research at the Institute of Development Studies, Brighton, UK

Herbert Hambati is Associate Professor at University of Dar es Salaam, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania

Lisa Ann Richey is Professor at Copenhagen Business School, Copenhagen, Denmark

Chris Büscher is Postdoctoral research fellow at the University of Turin, Turin, Italy

Paola Minoia is Associate Professor at the University of Turin, Turin, Italy

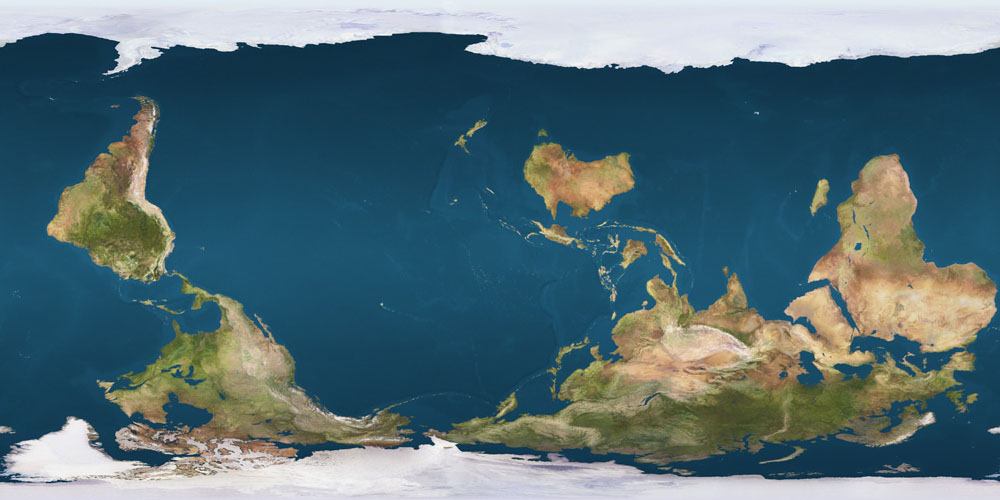

Image: Reversed Earth Map on Wikimedia

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of the EADI Debating Development Blog or the European Association of Development Research and Training Institutes.