By George Carter and Elise Howard

Women from Pacific Island countries have long been strategic and decisive leaders in climate negotiations, yet their stories are relatively unknown. Our recent work explores women’s leadership at the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in the making of the Paris Agreement 2015. We provide a snapshot of one year in three decades of climate negotiations and explore, how women played strategic roles to elevate the Pacific’s position on a global stage. As one seasoned negotiator representing Tuvalu stated,

“we have many Pacific island women in leading roles, stepping up in the international field representing their home islands and (our) region. Many of whom are excellent role models for others wanting to enter in the field.”

Pacific women have been integral for capturing global interest in climate change. Dame Meg Taylor, as Secretary General of the Pacific Island Forum, and Hilda Heine, as President of the Marshall Islands, have been staunch advocates, and acted as the face of Pacific diplomacy in recent climate change forums. In the activism space, to name only one among many examples, Kathy Jetnil-Kijiner is well-known for her poetry which has captured the world’s attention and raised awareness of the Pacific’s experiences of climate change.

The 345 strong delegation representing the 14 Pacific Islands states that negotiated the Paris Agreement had close to equal representation of male and female delegates. In part, this can be traced back to the strategic work of Marlene Moses, the Nauruan ambassador who led the Alliance of Small Islands States (AOSIS) coalition from 2011 to 2014. Recognising UN rules of state accreditation, Moses strategically selected lawyers from across the Pacific and accredited them under Nauru. These included Ngedikes ‘Olai’ Uludong from Palau, who was the Lead Chief Negotiator and would later become Palau’s Ambassador for Climate Change and to the United Nations; and Malia Talakai from Tonga, who was Deputy Chief Negotiator and would later become a senior UN official.

A Leading Force behind the Paris Agreement

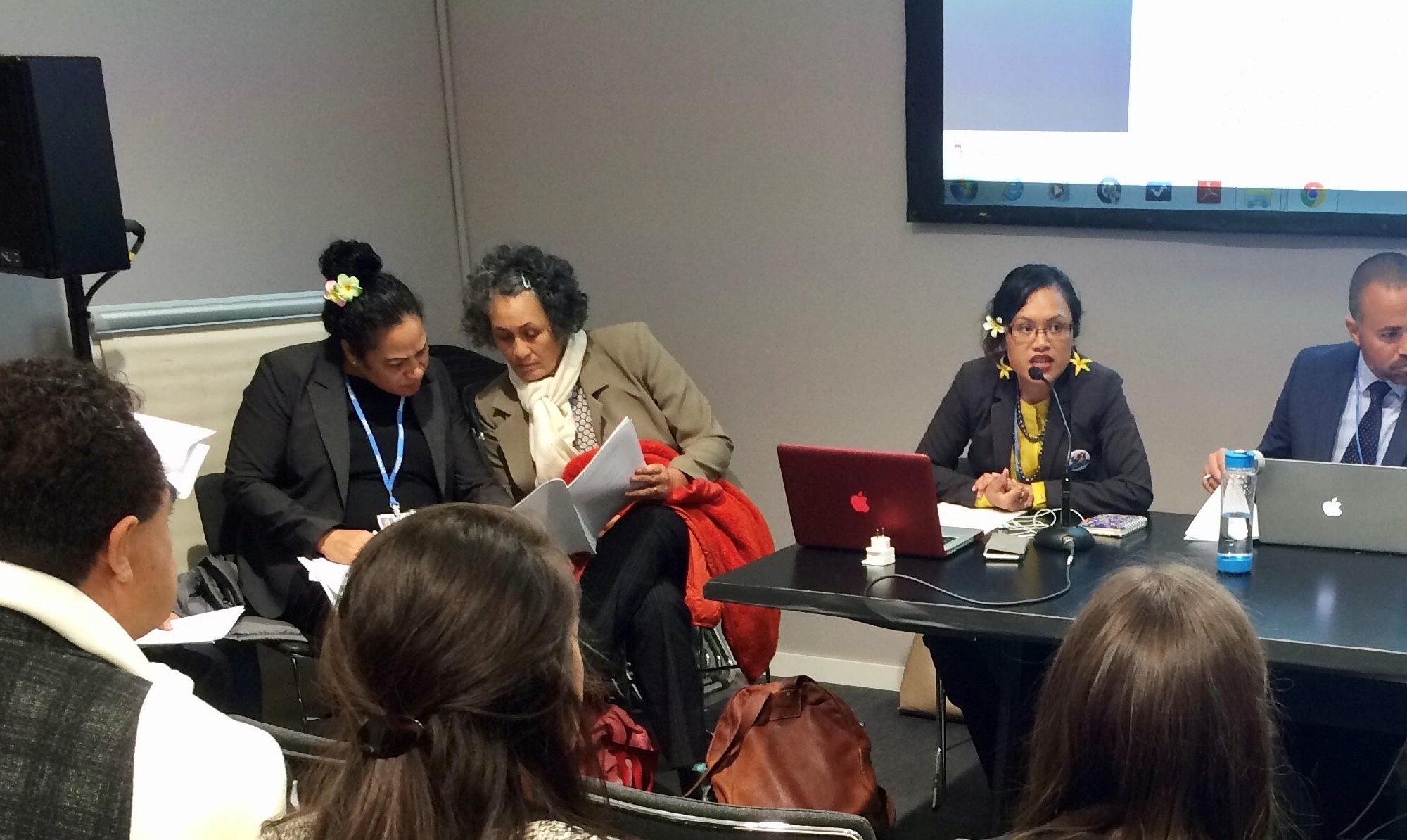

Women from the Pacific influenced the making of the Paris Agreement as lead national technical negotiators. Even more so, women were influential in building and a reaching the climate consensus in Paris as lead negotiators for coalitions or coalition coordinators. Pacific states and women representing the Pacific have been vocal in inter-state coalitions like AOSIS, the Least Developing Countries (LDC), Group of 77 and China (G-77) , and the Cartagena Dialogue and Climate Vulnerable Forum (CVF). In 2015, Palauan Ambassador Uludong spearheaded the Pacific’s work in the Pacific SIDS coalition as well as AOSIS. Samoa’s Anne Rasmussen and Tuvalu’s Pepetua Latasi were some of the many women coalition coordinators advocating for ambitious global climate actions. Rensie Panda represented a country not well-known for women’s representation in high level leadership and was a passionate negotiator for Papua New Guinea, AOSIS and the Coalition of Rainforest Nations (CfRN) coalition. The seasoned negotiator had over the years built a reputation as a confident and disciplined orator in the negotiations, a journey which was not an easy one. Her biggest challenge, she says was

”being a young woman negotiating in an area which I think is dominated by men. My biggest challenge was to rise up to this occasion and speak out and earn respect from those in the room. “

Linda Siegal and Diane McFadzien brought a wealth of technical and legal experience to the Cook Islands delegation (and have led and trained many women negotiators from the Pacific in recent years). This is underscored by the fact that the composition of the Cook Islands delegations was 90% women. Instrumental in training and coordinating Pacific negotiators has been the Secretariat of the Pacific Regional Environment Programme (SPREP) through the leadership and vision of Dr Netatua Pelesikoti and Tagaloa Cooper. Together with other regional officials in SPREP, like Nanette Woonton they have been committed in promoting and documenting the roles that Pacific women take on in climate change advocacy.

Despite this strong representation of women in negotiation teams, no woman from the Pacific acted as head of delegation in the 2015 Conference of the Parties (COP), although women from the Pacific, especially ambassadors, had filled this role in previous COPs and intersessional meetings. However, the Paris meeting was one of the most well-attended by heads of government, and in 2015, there were no female heads of government in the Pacific region. While some women acted in these roles – Ambassador Uludong and for Nauru, Minister for the Environment Charmaine Scott– this situation presented a real barrier to high-level women’s participation. Thus, the biased representation of men and women as heads of delegations was more indicative of the conditions that present significant barriers to women’s participation in national politics across the Pacific rather than women’s substantive contributions to climate change negotiation delegations.

The UNFCCC – A Space Designed By Men and Dominant Economies

The UNFCCC is a space designed by men and dominant economies. It is a site where Pacific Island nations and particularly women had to use innovative negotiating strategies to build alliances and increase their voice and power. The UNFCCC has introduced measures to improve gender balance in delegations and to place a greater focus on the gendered impacts of climate change. However, by and large these measures place gender as a separate issue to the main game of climate negotiations and leave responsibility for advocacy on the gendered impacts of climate to women. The implied assumption is that women who are representatives in climate delegations will represent women’s interests. Alternatively, women’s activist groupings outside of the main negotiations are expected to exercise influence from marginal positions.

Our research recognises that holding a position on a negotiation team requires in-depth knowledge of negotiations, science and international law, but not necessarily of social science or gender analysis skills. Rather than relying solely on women negotiators to represent women’s interests, all climate technical negotiators need to be held responsible for understanding the gendered impacts of climate change and the commitment to the actions needed to promote greater equality. Women have taken on multiple roles at climate conferences as representatives for their country, operating in an environment where negotiations are fast-paced and decisions will impact on national security, economic and environmental policies. Pacific women have undoubtedly thrived in this leadership task.

George Carter is a Research Fellow in Geopolitics and Regionalism at the Department of Pacific Affairs, and Co-Director of the Pacific Institute, at The Australian National University. His research interests explore island states from the Pacific’s influence in decision-making processes in multilateral climate change negotiations, climate security and foreign policy making. He teaches and researches various topics on the Pacific in international relations, diplomacy, development, security, climate change and environment, and Pacific Studies.

Elise Howard is a Senior Research Officer in Gender and Social Inclusion at the Department of Pacific Affairs at The Australian National University. Elise’s research explores women’s leadership in the Pacific, leadership pathways and the structural changes needed to build greater support for women’s participation in decision making, including on critical issues of climate change and security.

Image: George Carter