By Christine Lutringer

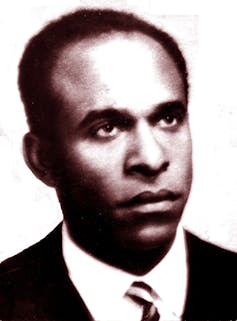

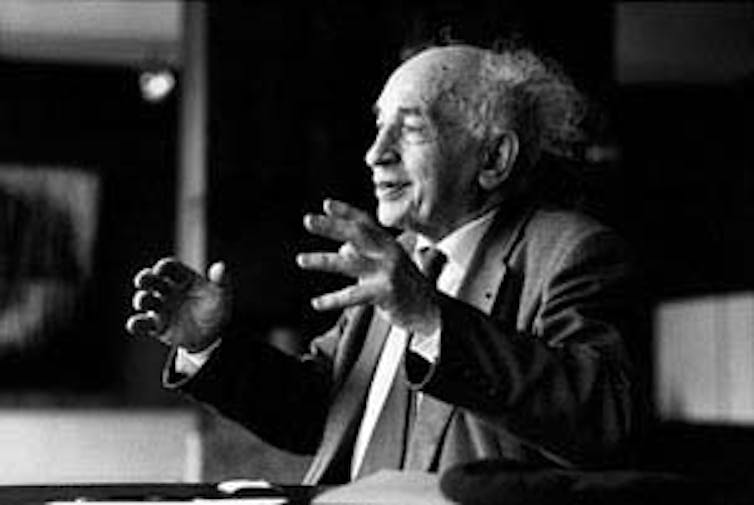

What do Alfred Sauvy, Jean-Pierre Olivier de Sardan and Frantz Fanon have in common?

Their works were all written in French and have made considerable contributions to our understanding of democracy and social change, whatever is the context. I explored this theme in a chapter of the upcoming book Building Development Studies for the New Millennium (Palgrave Macmillan), which analyses how Francophone academic literature played an important role in building development studies.

Some crucial contributions

Francophone academic literature holds great resources for social scientists delving into social and political change. Given its geography, it covers a wide range of economic, social and cultural settings, including France, Switzerland and Belgium; Quebec, New Brunswick and the Caribbean; North, Central and West Africa; the Indian and Pacific oceans; and Southeast Asia.

Observing socio-economic realities of the Francophone community opens up avenues of research and gives rise to analyses of development processes that may differ from Anglo-Saxon or other scholarships. With sociologists, anthropologists and political philosophers markedly influencing this field of studies since it was forged, Francophone works tend to give more emphasis to cultural and social values as well as to epistemological and methodological questions.

Some important pioneering work on development originates from Francophone authors: the very notion of the “Third World” was established by French demographer Alfred Sauvy in 1952. This also highlights the key role of non-economic disciplines in shaping Francophone development studies.

Studies originating from Francophone academic networks have had significant influence on development processes themselves because they have informed a certain type of development cooperation and a range of aid programmes promoted in particular by French, Swiss, Canadian and Belgian stakeholders.

Institutional linkages can often be traced between academic institutions and cooperation organisations. For example, the African Institute of Geneva (now part of the Graduate Institute) was created in 1961 to promote research on development and train future development practitioners, and also to conceive international cooperation projects for Swiss governmental bodies and NGOs.

Linking theory and practice

Francophone scholarship has called for reflection – and action – on democratic practices within and beyond states. This was accompanied by a key methodological change in the 1970s as research ceased to restrict itself to the intended beneficiaries of development interventions and recognised the plurality of actors and agents in development processes and the essential role of power relations.

To better understand the relationships between “theory” and “practice”, I also mapped the research landscape and examined in which context and on what terms institutions for development research were created. Conversely, it is interesting to observe the trajectory and institutional positioning of development studies journals.

For example, the only academic journal that is directly funded today by the French Agency for Development (AFD) is Afrique contemporaine. This should be understood in the context of the privileged links that French institutions have maintained with Francophone Africa

The contribution of French sociologists

My study highlights the distinct role of disciplines such as demography, sociology and anthropology in shaping Francophone development studies. In particular, it underlines the particular contribution of French sociologists in this field as early as the 1950s.

Sociological approaches of authors such as Pierre Bourdieu, Alain Touraine and Michel Foucault have deeply informed scholarship on development. The literature has therefore placed particular emphasis on notions such as trajectoire (trajectory) and pouvoir (power).

Interestingly, the early introduction of culture – and of cultural exceptionalism – in development theories also brought about a hiatus and hierarchy between the cultural realm and market rules.

The promotion of cultural diversity and of language identity have been key objectives for the Organisation Internationale de la Francophonie since its creation in 1970. France’s position was clearly articulated: cultural activities and artistic production ought not to be managed according to mere economic and financial criteria. In this perspective, cultural flows were to remain outside the purview of the market, which justified state interventions meant to restrict market laws in a range of domains.

Overall, Francophone development economics seems to have provided more critical approaches to development policies, locating analyses in more global or integrated perspectives compared with the Anglo-Saxon tradition.

It entered in conversation with other disciplines very early, partly because it gave more importance to the role of institutions in economic thinking. For example, François Perroux, one of the first French-speaking economists who theoretically engaged with development, used concepts such as asymmetry, disarticulation, domination and constantly aimed to test economic concepts empirically. His calls for engaging with other disciplines led to the creation of the journals Revue Tiers Monde and Mondes en développement, where economics was associated, in a multidisciplinary approach, with sociology, political science, demography and statistics.

(De)colonisation and scientific mobilisation

I also suggest that the lived experience and memories of colonisation and decolonisation fostered activist, political as well as scientific mobilisation.

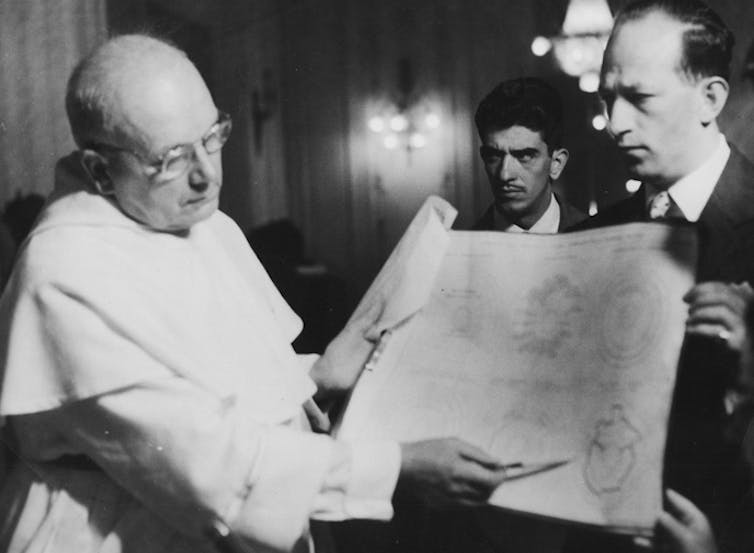

For example charitable actions across continents and activist engagement against the Algerian war led by personalities such as Louis-Joseph Lebret, economist and dominican priest who founded the Institut international de recherche et de formation éducation et développement (IRFED) in 1958, were followed by long-term development activities carried out by these movements and associations.

Centro Lebret USTA, Medellin, Colombie/Wikimedia, CC BY-ND

The production of Francophone scholarship has been facilitated by the extensive network of parastatal bodies and research institutions involved in activities of “cooperation for development”. For example, the Belgian and French systems of coopérants allowed to collaborate to an activity of collective interest abroad in lieu of military service. Moreover, the network of French research centres worldwide (some of which already created in the 1950s) has favoured the immersion of researchers in local realities.

Researchers who gained concrete experience of development also fed diverse ways of thinking. In Switzerland, Gilbert Etienne, a development economist whose fieldwork in Asia and particularly in India extended over a period of more than 50 years, was a vocal critic of both large development theories and anti-development ideologies. According to him, both led to a stalemate as they were unable to make sense of the more subtle ground realities, which were necessarily informed by historical, geographical and cultural factors and thus called for interdisciplinary research.

Development Projects Observed, Albert Hirschman’s influential book published in 1967, was key in shaping the analysis of development processes among Francophone thinkers as well.

A Francophone renaissance

Considering the effects of globalisation and the multipolarity of the world, Francophone political scientists and sociologists are remarkable for their observation of economic, political, social change from below; one can cite the Groupe d’analyse des modes populaires d’action politique, which was created in 1980 by anthropologist Jean-François Bayart (Graduate Institute) to explore political situations from the perspective of subordinated actors rather than political power holders.

Studying these popular practices is key to understanding how authoritarian or democratic forms of government are experienced in everyday life.

Francophone scholars have largely contributed to “post-development” and “de-growth” theories. And today the French-speaking development community is raising concerns about the need to rethink the relationship between society and the environment.

![]()

Christine Lutringer is Senior Researcher and Executive Director, Albert Hirschman Centre on Democracy, Graduate Institute – Institut de hautes études internationales et du développement (IHEID)

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.