By Lucia Pradella

It is widely believed that Marx did not systematically consider the role of colonialism within the process of capital accumulation. According to David Harvey, Marx concentrated on a self-closed national economy in his main work. Although he did mention colonialism in Part 8 of Capital Volume 1 on the so-called primitive accumulation, this would only belong to a pre-history of capital, not to its everyday development. Based on a similar assumption, some postcolonial scholars criticise Marx for being Eurocentric, even a complicit supporter of Western imperialism, who ignored the agency of non-Western people.

If we read some passages from the Manifesto we could think that they are right. How can we explain otherwise Marx and Engels praising the role of the bourgeoisie drawing even the most barbarian nations into civilisation or the view that the liberation of colonised peoples depended on the victory of the revolution in Europe?

Before I start, let me make a short premise. In my first book I read Marx’s Capital in the light of his writings and articles on Ireland, China, India, Russia, and the American Civil War. At the time I believed that Marx only published a significant, but still limited amount of writings on the colonial question, those available in the Collected Works and in collections like Marx & Colonialism. But then in 2007 I worked at the Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences and Humanities, contributing to the complete edition of Marx’s and Engels’s writings. I thus “discovered” some of Marx’s 20,000 print page long notebooks (just to give you an idea, the printed notebooks alone would look like a new Collected Works). These writings show that Marx was interested in colonialism all his life, including when he wrote the Manifesto.

What came out of my reading? Let me start with the question of Marx’s field of analysis in Capital Volume 1. To analyse capital reproduction ‘in its integrity, free from all disturbing subsidiary circumstances’, Marx treats the world of commerce as one nation (1976: 727) and presupposes the full worldwide imposition of the capitalist mode of production. Does this mean that Marx analysed a “self-enclosed national economy” as Harvey and others believe? In my view, this abstraction means exactly the opposite. Marx’s positing a coincidence between the national and global levels is a premise for conceptualising the world market, which includes both internal and foreign markets of all nations participating in it. This abstraction makes it possible to include expansionism into the analysis of capital accumulation. In this framework, a country’s economic system is not confined within its national borders but consists of all production branches where capital is freely transferable, including the colonies and dependent economies.

Accumulation of capital happens internationally

Accumulation, for Marx, leads to the concentration and centralisation of capital internationally, including through the rise of big corporations and financial capital. Processes of violent dispossession of direct producers, forced market expansion and colonisation do not belong only to a pre-history of capital but are constitutive of the process of capital accumulation on a global scale. Following the period of “primitive accumulation”, however, it’s the power of the state that depends on capital, rather than vice versa. The competitive process of capital accumulation tends to concentrate higher value-added production and capital in the system’s most competitive centres, leading to a forced specialisation of dependent countries in lower value-added sectors, repatriating profits extracted in these countries, and leading to forms of unequal exchange between nations with different productivity levels.

To make up for their losses, capitalists in less developed nations increase the amount of absolute surplus value they extract from the working class. They do so by lengthening and intensifying the working day and, crucially, pushing wages to below the value of the labour power. Marx himself had these processes of “super-exploitation” in mind when he affirmed that wages in India were depressed even below the worker’s modest needs (CW31: 251).

One of the main ways in which capital counteracts the fall of the rate of profit, for Marx, is by expanding its ‘field of action’ and swelling the ranks of the global reserve army of labour. This process was particularly evident in the case of British domination of Ireland. Along with slave-grown cotton in the United States, primary production by impoverished Irish farmers was one of the pillars of English industry. Irish dispossessed peasants, moreover, fled the country in search for better conditions, swelling the ranks of the unemployed and underemployed in British industrial centres. Processes of colonisation and impoverishment in Ireland thus affected the condition of the working class in England as well, from both material and moral points of view. Workers in England did not just compete against each other. The anti-Irish racism instigated by the English ruling class fomented antagonism between Irish and English workers, the latter being seen by the Irish as complicit in English domination over Ireland. And this antagonism, for Marx, “is the secret by which the capitalist class maintains its power.”

“Marx was aware of the role of racism in capital reproduction”

By looking at Britain as an imperialist economy, by conceptualising the process of capital accumulation on a global scale, Marx grasped the inter-linkages between workers’ labour and living conditions internationally. Processes of imperialist expansion are not external to the condition of the working class in imperialist countries but are inter-related. Marx was also aware of the role of racism within the process of capital reproduction.

It was in the wake of the American Civil War and European workers’ solidarity with the struggle for the abolition of slavery that the First International Workingmen’s Association was born. Its very project emerged because workers and trade unionists understood that only by organising internationally could they oppose the means the bosses used to smash their organisation: moving production to countries in which wages were lower, or “import” immigrant workers from abroad to put workers in competition to each other. Of course, at the time all this happened at a smaller scale, since industrial production was concentrated in Europe and the United States.

If this is the case, would Marx and Engels today repeat the same arguments they advanced in the Manifesto? The point is that Marx’s position on these issues changed over time. Over the years he integrated imperialism into his critique of political economy and overcame his unidirectional view of international revolution. He realised that material improvements in the condition of the working class in imperialist countries could make international solidarity more difficult. And colonised peoples were not passive actors that had to wait for the industrial proletariat in Europe to wake up and overthrow capitalism. They had their own initiative.

At the very beginning of 1850 Marx and Engels greeted the social upheaval in China: by enhancing the factors of crisis in Europe, the Chinese revolution could spark a social revolution in Europe itself. Marx also supported the Indian Sepoy uprising against British colonialism insisting that, independently of the insurgents’ consciousness, it had a national character. At the end of the 1860s, moreover, he changed his mind on the relationship between proletarian struggle in England and Irish liberation. The working class in England had to support the Irish struggle for independence not as a humanitarian issue, but as the precondition for its own emancipation. This was the condition for building real working-class unity in England as well. “The lever must be applied in Ireland”.

Not only, therefore, has Marx something to say about the role of colonialism within the process of capital accumulation, this has also very much to do with the “secret” of working-class power.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of the EADI Debating Development Blog or the European Association of Development Research and Training Institutes.

Lucia Pradella is Senior Lecturer in International Political Economy at King’s College, London. She is co-organiser of the Seminar in Contemporary Marxist Theory at King’s College

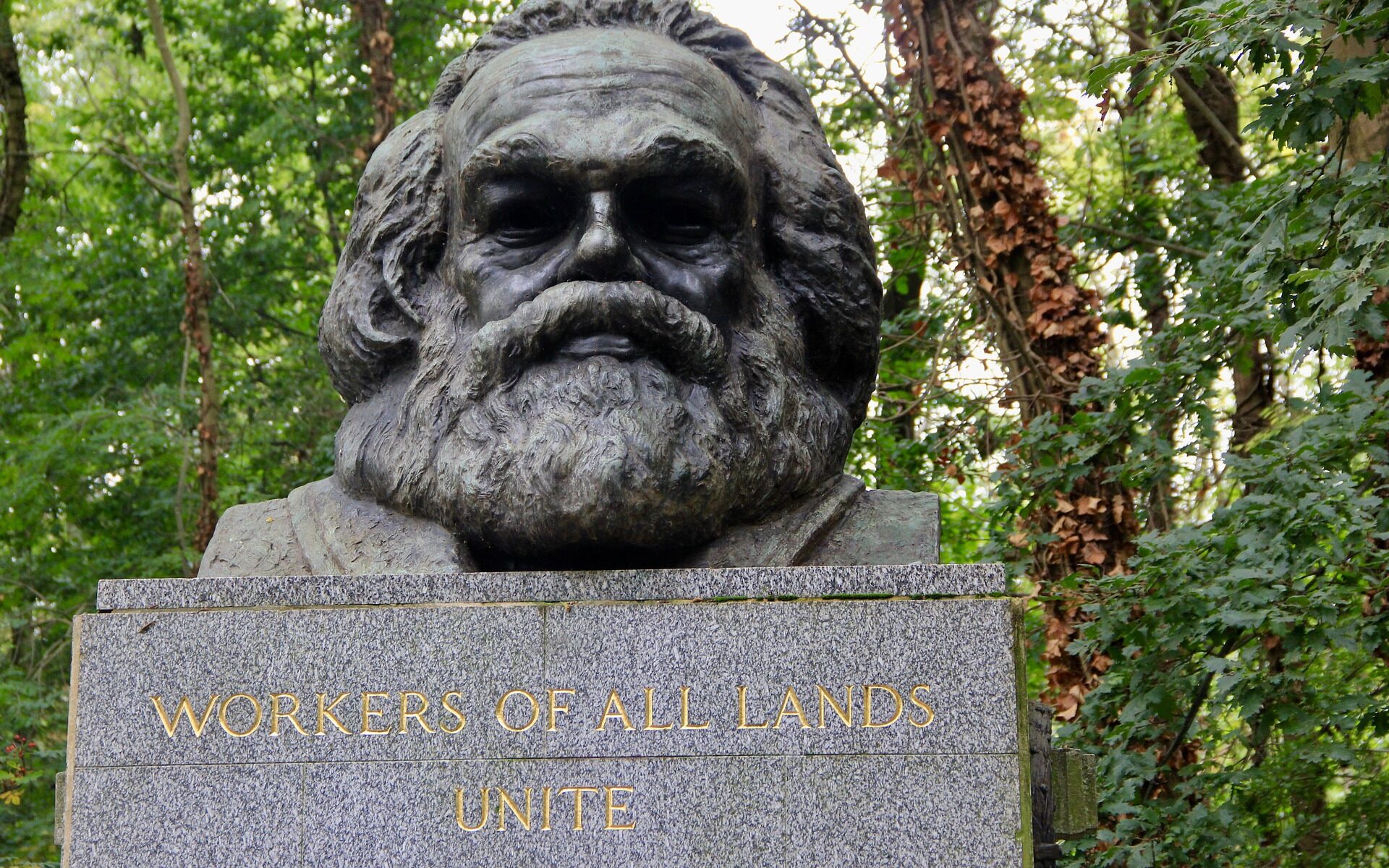

Image: Mary Bettini Blank on Pixabay