By Julia Schöneberg

My research focusses on decolonial approaches to knowledge production and pedagogy, especially in the context of “development”. Development is a contested term that has been filled with different, sometime contradictory meanings. I am convinced that one cannot meaningfully speak about “development” without seriously considering critique and arguments brought forward by decolonial scholarship. Essentially, this means to acknowledge and to confront the ongoing impacts and legacies of colonial rule in all realms of academia, society and politics. As Olivia Rutazibwa forcefully argues, it is dangerously wrong to start telling the story of development from the infamous “Point 4” Truman speech in 1949, but necessary to take Aimé Césaire’s disturbing yet precise “Discourse on Colonialism” as the grounding point instead.

Despite the fact that there are increasing attempts to “decolonise development”, much of academic debate is still concerned with questions of how to fix development, how to make approaches, projects and interventions more applicable, but seldom on questioning the complex web of who defines “development”, who practices development, with what means and to what ends. Most importantly, why do Western universalist idea(l)s of progress and growth continue to occupy the core of all deliberations? Without attempting to be conclusive, I want to highlight what I see as first careful steps towards approaching development studies with a decolonial lens, starting in the areas of research, teaching and collaboration.

A cross-cutting theme through these areas inevitably is positionality. How do I, as a privileged, well-educated white middle-class German woman situate myself in the field I am thinking about, the interactions I am involved in and the knowledges I aim to contribute to? Questioning my own positionality cannot mean to feel paralysed and to flagellate myself for the wrongdoings of my origin. It means to seriously consider the colonial legacies that continue to be at play and actively attempting to counter them, especially in those three areas that constitute my daily work as a development studies scholar.

Researching

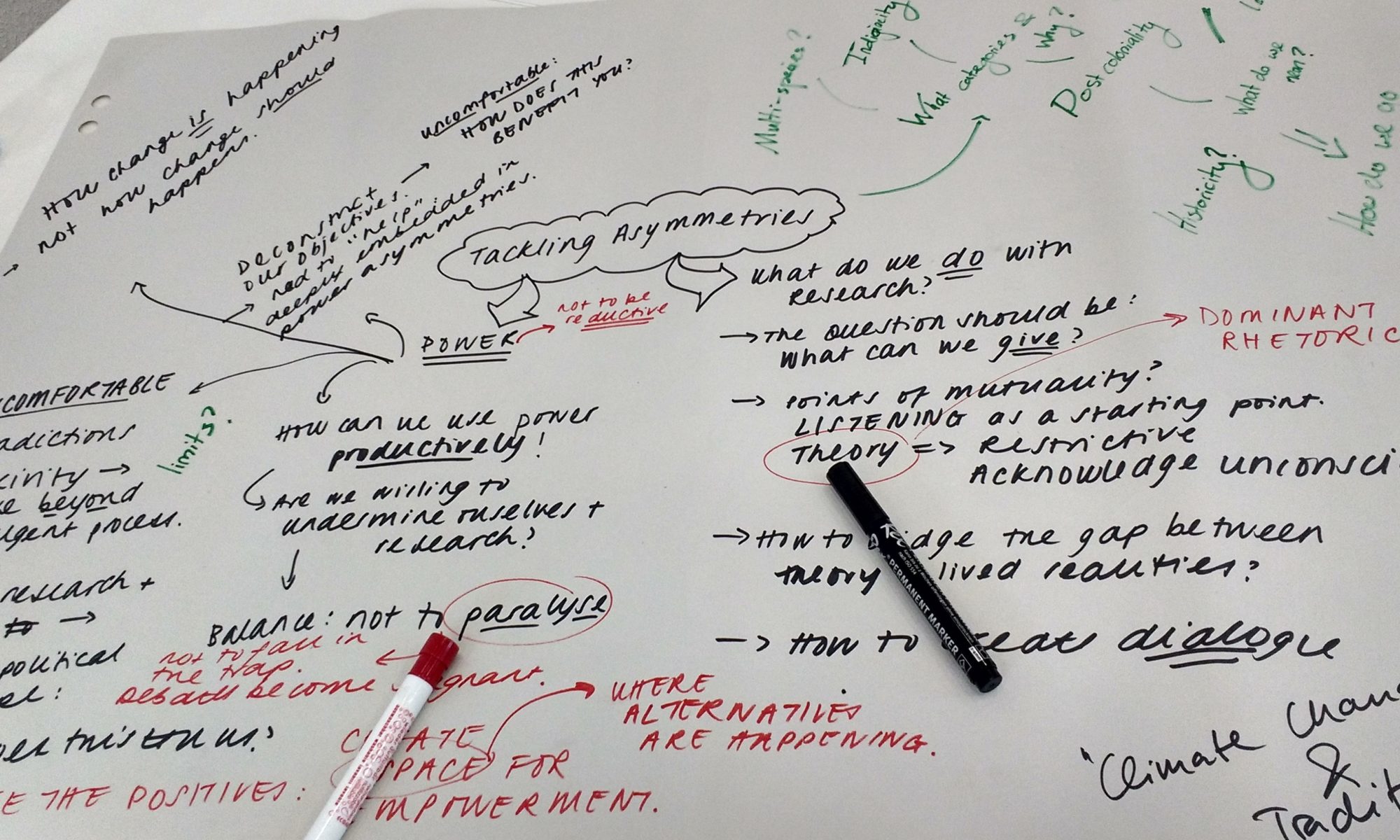

In a recent workshop on critical scholarship, participants shared the concern of what they, especially in conducting empirical research and being in the role of extractors of knowledges, can give back to those who share with them. Chris Millora has suggested reciprocity as a fundamental research ethics. Siti Maimunah and Enid Still, in positioning themselves as scholar-activists, see their research within a “politics and praxis of care and embodied, situated forms of knowledge production, [which] enables us to reflectively and collaboratively engage with the power inscribed within place and upon bodies.”

Teaching

Of course, diversifying your reading list is not enough, but it is a start. Am I just teaching the same old, white men as I have been taught in my own degree or are there authors from elsewhere? Are they diverse in gender and origin? Don’t get me wrong: diversity also means that those white guys, who are in themselves certainly not homogenous, are included, as Witold Mucha and Christina Pesch make clear. They can – and should – still be taught, just not to the exclusion of other thinkers. It is important to set their, oftentimes overt, racism or misogynism into the appropriate historical context, juxtaposed with streams of thought from other parts of the world.

And there’s no excuse. The colleagues at Global Social Theory have already done much of the work.

Then, ask yourself how do you teach “development”. Challenge Eurocentrism in Social Science Research and Teaching, like Sebastian M. Garbe demonstrates, or attempt to explore how to ‘unlearn’ ways of knowing as outlined by Zeynep Gülşah Çapan. There are many ways to decolonise teaching pedagogies.

Collaborating

Research partnerships are quite often, despite claiming otherwise, not functioning on equal levels. In addition to the persistent asymmetry of funds in building research collaboration with colleagues beyond Europe, I need to be conscious of epistemic asymmetries. As Nora Schröder and Michaela Zöhrer convincingly argue, “mutual learning is possible not despite of but thanks to asymmetries between the people involved” – on the condition that we are not blind to underlying power relations and actively counter them.

Finally,

In attempting to find my space and legitimacy as a development scholar, I continue to be inspired by those who walk before and alongside me. I believe that this community, mutual learning, respect and critical but constructive contestation is a first step to pursuing a development studies of benefit to all – with a decolonial lens.

Julia Schöneberg is post-doctoral Research Fellow at the Department of Development and Postcolonial Studies at the University of Kassel, Germany and Visiting Researcher at ISS in The Hague. She is co-founder of Convivial Thinking.

This blog post is part of the series on the EADI edited volume “Building Development Studies for the New Millennium to which Julia has contributed the chapter “Imagining Postcolonial-Development Studies: Reflections on Positionalities and Research Practices”