By Mark Akkerman

Over 1000 refugees have died this year trying to cross the Mediterranean Sea. According to recent statements by the UNHCR probably twice as many migrants died crossing Africa, largely outside the view of European press and public. Others end up in dire circumstances, in refugee shelter or detention camps inside and outside Europe, or living in illegality.

This is not a coincidence with, but a consequence of European migration policies that aim at keeping or getting migrants out. Border security is strengthened and militarized, both at Europe’s external borders and, under heavy pressure from the EU, in neighbouring countries to prevent refugees from reaching the European borders at all. Meanwhile, NGO rescue missions in the Mediterranean and other forms of solidarity with refugees are increasingly hindered and criminalized by EU and member states’ authorities. This all leads to more violence against and risks for refugees, who are forced to look for other, often more dangerous, routes and are driven into the hands of criminal smuggling networks.

A very visible, though highly symbolic part of these policies is the construction of walls and fences at borders. Since the end of the Cold War European countries have built about 1000 kilometres of land border walls, most of them constructed from 2015 on, the report ‘Building Walls‘ revealed last year. Next to this, Frontex operations ‘”maritime walls” in the Mediterranean and between the African mainland and the Canary Islands cover some 4750 kilometres of sea. Meanwhile, “virtual walls” are used to track and identify migrants to be able to deport them to their countries of origin. These include (biometric) identity databases, information exchange systems and the border surveillance system Eurosur).

Spending on border walls

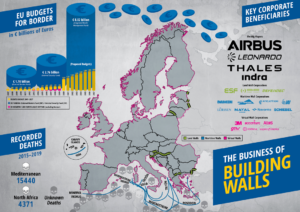

In a new report entitled ‘The Business of Building Walls‘, the Transnational Institute (TNI), the Dutch campaign against arms trade “Stop Wapenhandel” and Centre Delàs delve into the costs of and corporations involved in these different kind of walls. The EU and its member states have pumped billions of euros into these walls. Spending by member states on land walls, which are usually not funded by the EU, is estimated at at least €900 million. Frontex operational costs also run into hundreds of millions of dollars, while spending on the virtual walls has been about €1 billion.

In the next years, during the next EU budget cycle (2021-2027) these costs are bound to increase. The new Integrated Border Management Fund, which will finance border security measures by member states /including equipment purchases -, has a budget of over €8 billion, almost twice as much as its predecessors the External Borders Fund (2007-2013) and the Internal Security Fund – Borders (2014-2021) combined.

Frontex will also see a huge budget increase to more than €11 billion, of which the European Commission has earmarked €2.2 billion to buy or lease its own equipment. And while there is no complete overview of the planned spending on the databases and Eurosur yet, this will amount to at least another €900 million.

Double profits: arms exports and walls business

Large European arms companies, like Airbus, Leonardo and Thales, have been and most likely will remain the main beneficiaries of this spending spree. They provide goods and services for all kinds of walls. Helicopters are the most important business for Airbus and Leonardo here, while Thales provides radar, for example for border patrol ships. Thales is also heavily involved in biometric and digital identification, especially after acquiring Gemalto earlier this year. These three companies, cynically, are also important arms exporters to some origin countries of refugees, thereby fueling the reasons for people to flee from wars, internal conflicts and repressive regimes and human rights violators outside Europe.

Many other companies focus on a certain types of walls: Most land walls are built by local construction companies, whereas the Spanish company European Security Fencing provided razor wire for the fences around the Spanish enclaves Ceuta and Melilla in Morocco, the fence at Calais and the fences on borders of Austria, Bulgaria and Hungary.

Vessels from the Dutch shipbuilder Damen have been deployed to Frontex operations and the military Operation Sophia before the coast of Libya.. Damen has also controversially sold patrol ships to non-European Mediterranean countries, including Libya and Turkey. Many other patrol ships that are used are built by national shipwarfs in the respective EU member states.

For the virtual walls, French IT-company Sopra Steria has secured a string of EU-contracts, worth over €150 million, for the development and maintenance of fingerprint database Eurodac and identity information exchange systems. GMV, a Spanish technology company, has received a succession of large contracts for Eurosur, , worth at least €25 million since its testing phase in 2010.

Framing migration as security threat

The underlying narrative for the policies these companies profit from is the framing of migration as a security problem and a threat to the ‘European way of life‘. This narrative has been pushed by the military and security industry through effective lobbying, in which representatives of this industry present themselves as experts offering the solution: the use of their goods and services. It ignores that forced migration is predominantly a political and humanitarian problem that requires answers on these levels. For this, the EU at least needs to offer shelter and support to refugees and, most of all, needs to work on eliminating the reasons people are forced to flee. This would mean a whole overhaul of EU international policies, including stopping arms exports and military interventions, as well as taking serious steps regarding climate change and ending unequal trade relations.

Mark Akkerman is a researcher at Stop Wapenhandel (Dutch campaign against arms trade) and the Transnational Institute (TNI).

Image: Eagle-Wings on flickr